ACCORDING TO someone, there are two types of people in the world: Those who believe that there are two types of people—and those who don’t. Among the former was the Greek poet Archilochus, who believed that people tend to be either foxes or hedgehogs. Foxes are centrifugal, hedgehogs centripetal. “The fox knows many things,” he said, “but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

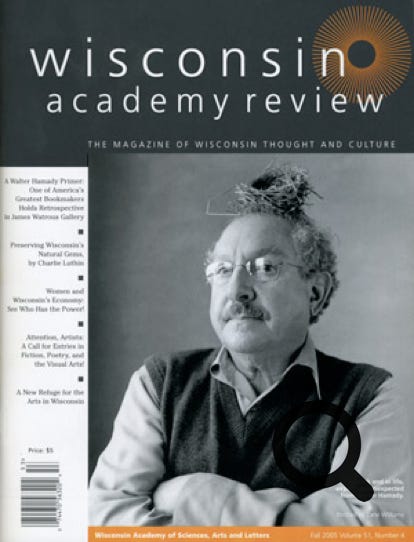

For years I have admired the work of Walter Hamady (his extraordinary handmade letterpress books, his collages and assemblages), but now and then I’ve asked myself: “Is Walter a fox or a hedgehog?” A fox is uncommonly clever, resourceful and adaptive. Indeed, it has such agility that we never know what to expect from one moment to the next. A hedgehog, on the other hand, moves slowly and determinedly: it survives by reliably standing its ground, albeit encased in an armor of barbs. Both these “cognitive styles” have advantages and disadvantages, and, throughout human history, both have repeatedly proven to be enormously effective.

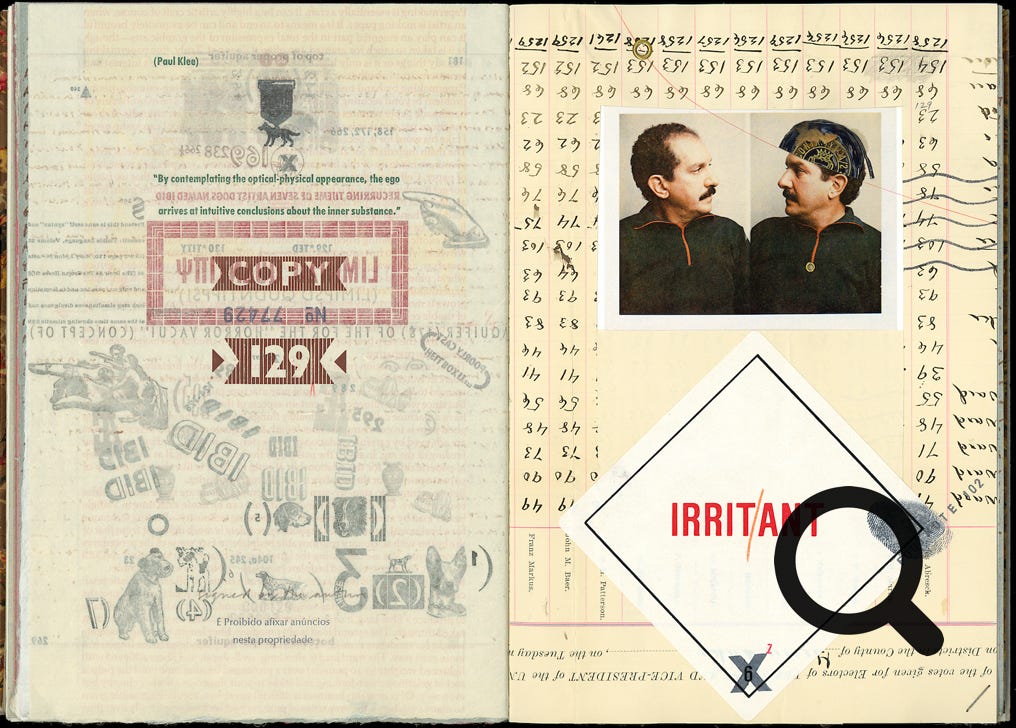

It goes without saying that Walter is in many ways fox-like. For example, he is what is called a polymath: His interests, skills and insights are so wide-ranging, so diverse and unpredictable that almost every thing he does defies easy classification. At times, his labyrinthine flights are reminiscent of a Persian carpet, and, at other times, of the “crazy quilts” that farm wives made from the leftover scraps of conventional quilts.

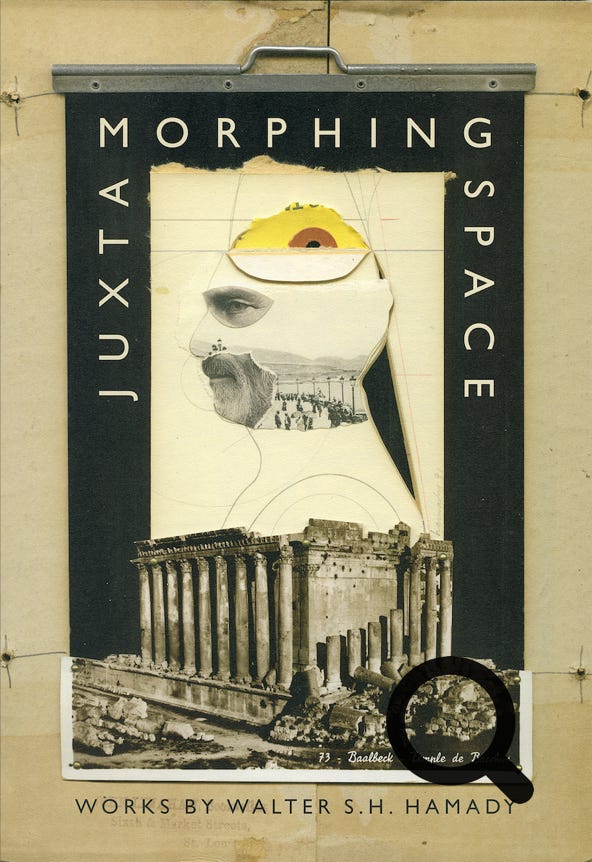

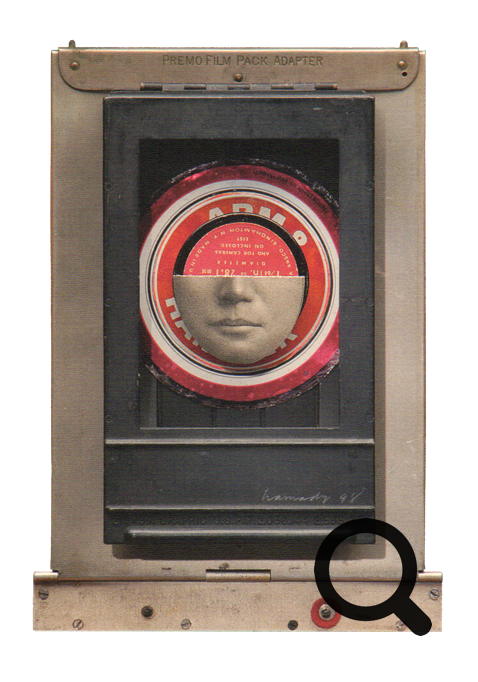

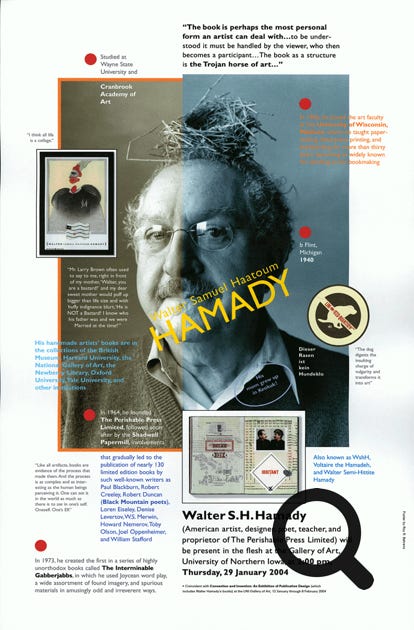

Walter’s never-ending quests (the term “quixotic” comes to mind), his craving for experimentation, and the complex and bewildering forms he concocts have sprung from “juxtamorphing” art with literature, typography, teaching, parenting, letterpress printing, papermaking, book arts, collage and assemblage. “I think all life is a collage,” he has stated, and surely he himself is that—a collage of antipodal cultures—in the sense that he resulted from the (short-lived) marriage of a “loving intelligent mother” who was “a pediatrician, intellectual and bibliophile” from Keokuk, Iowa, and a long-despised Lebanese father, who abandoned his wife and children, whereupon Walter’s role model became his devoted Jidu (his paternal grandfather, Ralph Haatoum Hamady), “a wonderful man [from Baakline, Lebanon] who came to America as a teenager in 1907.”

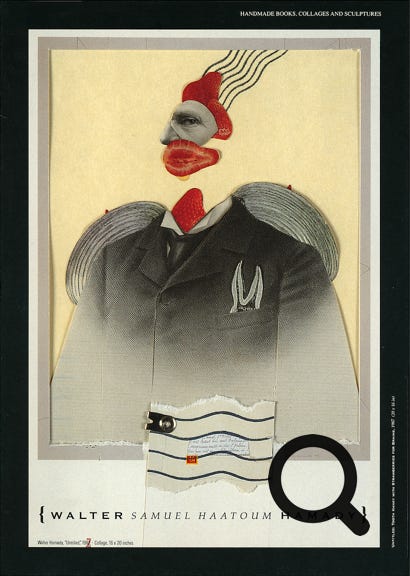

Like a storybook fox (a fleet-footed, wily survivor), Walter is frequently misleading, even evasive. In talking or writing or working, at one moment he is here, a second later, over there. In truth, he is always and simply himself: Walter Hamady, the founder and proprietor of The Perishable Press Limited (begun in 1964) and the Shadwell Papermill, and Emeritus Professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. But he also puts on the chimerical masks of Walter Samuel Haatoum Hamady, Walter Semi-Hittite Hamady, WshH, Voltaire the Hamadeh, or a roster of other identities that hit and miss, miss and hit—on purpose and all at the same time.

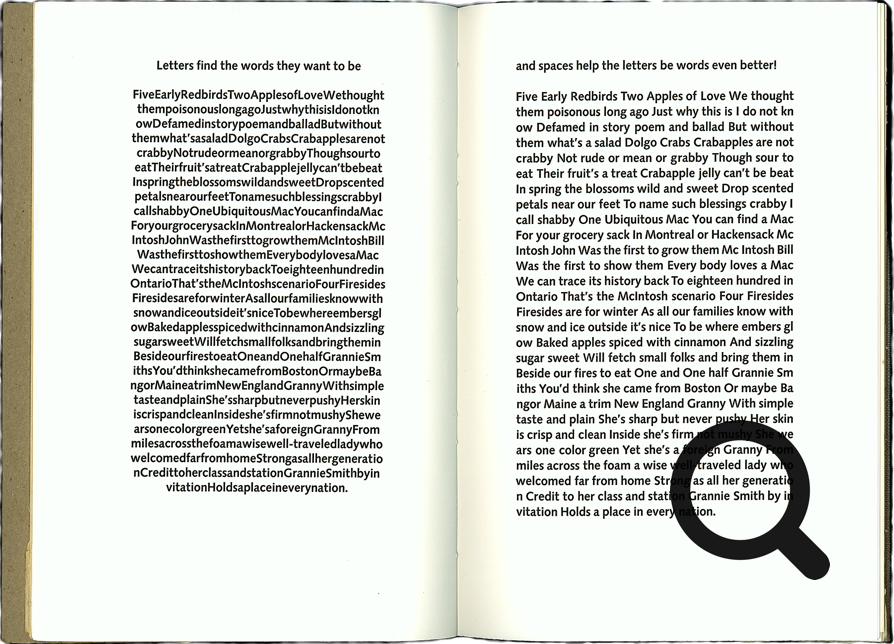

Like others whom we classify as “creative,” Walter is all but driven by an urge that sociologists call “the play instinct.” This is especially evident in the lack of restraint in his toying—his “juxtamorphing”—with anything and everything (materials, techniques, objects and words), which, in its verbal forms, results in a boundless outpouring of puns, spoonerisms, malapropisms, and deprecatory nicknames (I don’t think any two of the hundreds of letters he’s written to me have ever been addressed to the same person—much less the right person). In that sense, he is not unlike Mark Van Doren’s father (as recounted in that writer’s autobiography), an Illinois farmer who delighted in “call[ing] things by the wrong names—or, it may be, the right ones, fantastically the right ones. Either extreme is poetry, of which he had the secret without knowing that he did.”

While he is undoubtedly crafty, like a fox, one can also persuasively argue that Walter is a hedgehog. Think about it: How many people still practice (in earnest) the archaic technology of letterpress printing? And of those, how many do it for reasons that are not primarily nostalgic or therapeutic, but radically experimental? How many people write letters today—real, honest-to-God letters, not e-mail, and surely not those insufferable calls on a cell phone? How many are seriously interested in producing handmade paper (Walter was a pivotal contributor to the recent resurgence of interest in that), but, in so doing, apply it in wholly unorthodox ways (for example, if you can believe this, he once shredded a copy of my first book on Art and Camouflage, long out of print and extremely rare, to make it into paper pulp with which he “camouflaged” my book in a page of one of his own books)?

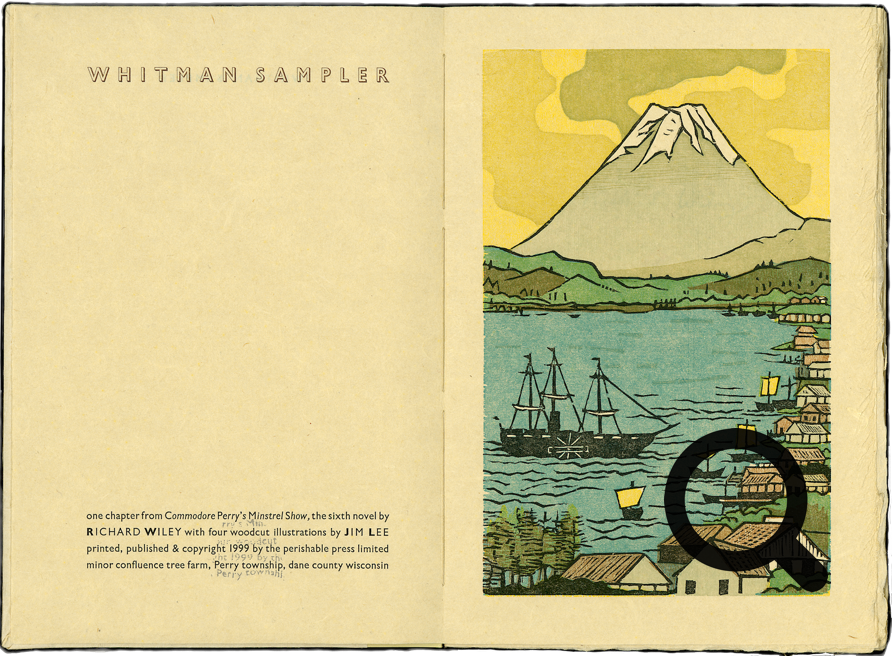

Finally, how many people have Walter’s command of page layout, or his understanding of typesetting, printing, paper, and book design? At the same time, his achievements in all these areas distinctly stand alone because he is compelled to be a “sort-crosser” (to use Colin Turbayne’s term), a person who blatantly pushes the bounds of our most inviolable traditions. Nowhere is this more richly shown than in his so-called Gabberjabbs, an on-going series of letterpress books that have no equivalent in the category of handmade artist’s books.

To repeat: The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. If Walter is a hedgehog (as well as a fox), what is the “one big thing” he knows? I think I’ve known the answer to that from the moment I first saw his work at an exhibition in the mid-1970s. Being diversionary, he rarely straightforwardly lectures about his various “trade secrets,” but he frequently alludes to them in his letters, his writings, his lectures, and (by tacit example) in each and every work he makes.

He also offers clues about his modus operandi whenever he talks about teaching, which he practiced sincerely and admirably at the University of Wisconsin at Madison from 1966 until his retirement a few years ago. For example, in a document he drafted in 2003, titled “Hamady’s Problems / A Pedagogical Ramble,” among his recommendations to students is that traditional principles “should be studied, understood thoroughly and forgotten.” In another document, which takes the form of his own spurious obituary, he recalls of teaching that “if successful, by the end of each semester, the students thought that all they had learned had been invented by themselves…”

In other words, the “one big thing” that Walter (Hedgehog) Hamady knows is that teaching and art-making and letter-writing and parenting and being married—along with all the other ilks of daily experience—are interactive and collaborative; they are exchanges that never hold still. As much as we might otherwise want, our lives are rarely preordained, but are distilled from an undefined, on-going flow that is richest when all its participants give to its construction and interpretation. He says this most explicitly when he quotes the age-old adage that life is primarily about “the journey, not the destination.”

Everything Walter does is what he himself has called an “autodidactic tutorial” (an occasion for self-instruction) from which the most valuable lesson to learn is that being alive is more meaningful when it is unanticipated and fortuitous, rather than rigidly planned in advance. “If you know ahead of time where you are going in this, then it isn’t worth the trip,” Walter has said. “Like all artifacts, books [like collages and assemblages] are evidence of the process that made them. And the process is as complex and as interesting as the human beings perceiving it. One can see it in the world as much as there is to see in oneself. Oneself. One’s Elf.”

•••